In South Australia

In Kingscote Samuel Stephens takes advantage of the John Pirie sailing to Hobart to write to George Fife Angas, enclosing a copy of his private journal. The tone of this letter is somewhat defensive. Stephens stresses that he has ‘had a great deal to contend with’, and admits that he may well have ‘erred in some things’, but assures Angas that he is mindful of the need to pay a company dividend as soon as possible. This seems somewhat ambitious, even fanciful in the circumstances, but Stephens has plans for an ‘Agricultural Establishment’ at Yankalilla and recommends that a Bay Whale Fishery should also be established. ‘Fishing and Sheep Farming will be our two grand sources of Profit’, he writes, ‘Merchandise (trade and commerce) the next. He is also aware that the time for the sale of the 563 ‘spare Acres of town land’ is near, but worries that he may well run out of cash in the interim. Unfortunately this is the last we hear of Samuel Stephens directly. If he continued to keep a private journal, it does not seem to have survived.

Colonel Light, Woodforde and Pullen meanwhile, spend a frustrating week scouring the coast for the safe harbour a certain Captain Jones had described previously. In increasing anxiety they investigate every likely inlet from Holdfast Bay to the top of the gulf, but cannot find anything that seems to correspond to the description they have. Light alternates ‘between hope and fear’, but finds some consolation in his first glimpses of the Adelaide Plains. ‘I was enchanted with the extent of the plain to the northward of the Mount Lofty range’, he writes and stays glued to the looking glass as they sail slowly down the coast.

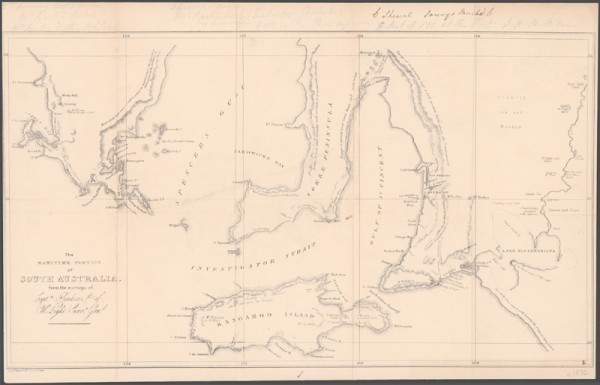

The maritime portion of South Australia from surveys of Captn. Flinders and Col. Light, Survr Genl.

At sea

After some rough sailing conditions the weather abates enough for the Africaine to speak to a schooner on its way to the Swan River Colony. Robert Gouger learns that the main cargo on board is ‘spirits of various kinds’ – 100 puncheons to be precise, or one puncheon for every person at the Colony. Since a puncheon could hold anything from 72 to 120 gallons, Gouger is not surprised to learn that the main problem at this colony is drunkenness!

On the Buffalo resentment mounts at the Governor’s many changes of course. They are short of water and Stevenson is convinced that they have no choice but to call in to Rio, but Hindmarsh vacillates, and for several days alters course to steer in another direction. Stevenson despairs. ‘The misfortune is that many may suffer bitterly for one man’s indiscretion’, he writes.

Language warning: Please note that some of these sources contain language which is today considered offensive. It has been retained as it is part of the historical record and evidence of past attitudes.

Comments or Questions: