In South Australia

The week begins with the long-awaited arrival of the Cygnet. Sadly this is the last we will hear of Boyle Travers Finniss, as his diary ends with the arrival on Kangaroo Island on 11 September. From his last brief entry however, we learn that Colonel Light has left a letter for Kingston, instructing him to proceed directly to Port Lincoln after off-loading his stores at Fresh Water River.

Others are also about to leave the Island. Captain Morgan is busy preparing the Duke of York to sail, filling casks with fresh water, repairing the boats and ‘other jobs as needful’, but he still finds time to pray every night and to remember his ‘beloved wife and children’. Elsewhere on the Island John Brown is busy building cottages for himself and his men near the Freshwater Lagoon. He is having trouble with the stock straying, especially the merinos. But at least all seems peaceful. Samuel Stephens visits briefly, but is soon off to the mainland. Then towards the end of the week Brown’s men all go into Kingscote to collect their wages, leaving him ‘quite alone’ as he writes. This must have been an unnerving experience after all the weeks in close confinement at sea

Over on the mainland Colonel Light, Dr Woodforde and William Pullen are exploring the coast between Rapid Bay and Yankalilla. They land at an inlet, which Light promptly calls Finniss Valley, (now Second Valley) and walk through the rich countryside to Yankalilla, an Aboriginal name that Light decides to retain. Once again they are charmed by the ‘park like appearance’ of the countryside and speculate that it will be well suited to agriculture.

In the diaries of Pullen and Woodforde this week we hear much about some members of the local {tooltip} tribe ,{end-text}Ramindjeri Encounter Bay{end-tooltip} who come with the sealer Cooper to meet the newcomers. Pullen describes a ‘corrobory’, but there are some puzzling elements to his description, and to some of the other comments he makes (about infanticide for instance), suggesting either that he revised his description later, or that he had read accounts of such practices elsewhere.

Woodforde also comments on the Aboriginal men from the perspective of a doctor. He notes signs of the ‘ravages’ of smallpox, records that two of the men have ‘congenital malformations’, and notes the existence of ritual scarring (described as tattoos). They are all puzzled by the sight of many burnt tree tops, surrounded by rich, green growth. They have heard that the Aboriginal People fire the country, but are inclined to attribute the burning to lightning strikes (‘the electric fluid’) instead.

At sea

The Africaine is approaching the Cape and all on board are busy making lists of things they want to buy. It is much colder and the Gougers find they don’t have warm enough clothing, but in other respects they are very comfortable in their cabin. Robert Gouger gives us a lengthy description of the various ‘conveniences’ of their situation, which he intends as guidance for other wealthy travellers in the future.

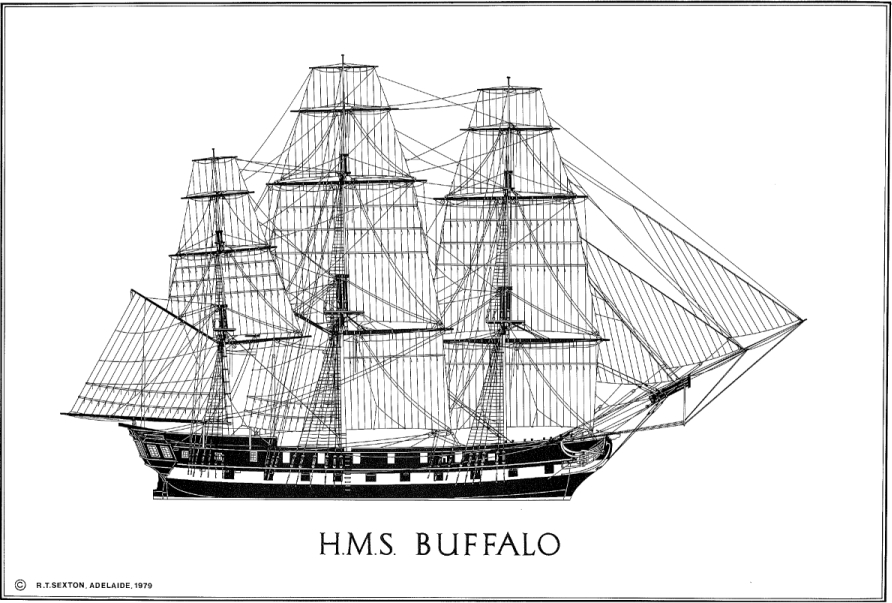

The Buffalo meanwhile has almost reached the Equator and everyone on board is preparing for the ritual visit of Neptune. Stevenson continues his litany of complaints against the Governor. He and James Hurtle Fisher seem to agree with one another on many things, notably this week on the importance of establishing a public library in the new province. Hindmarsh evidently does not agree: ‘what good will books do our Colony’, he apparently comments. But Stevenson and Fisher intend to persevere. There is another interesting comment in Stevenson’s diary entry this week. The male passengers are all required to practise military drilling, so that an additional armed force will be available if required, but Stevenson is vehemently opposed to any such force being directed against the Aboriginal population. A ‘hostile shot shall never be fired against them if I can help it’, he writes. His comment suggests that Stevenson supports the views of radical reformers at home where this issue is concerned.

Sadly the week ends in tragedy. Just as everyone prepares for the crossing the line ceremonies that night, a young sailor, Story, ‘the only support of a widowed mother’, falls overboard while taking {tooltip} soundings {end-text} The action or process of measuring the depth of water with a sounding line, a line marked at intervals of fathoms and weighted at one end. A fathom is a unit of length equal to 6 feet (1.83 metres). {end-tooltip} for a shoal marked on the Admiralty charts. Although they put a boat out for him within a few minutes, he is lost, probably because he cannot see the ship in the darkness. Stevenson is sickened by the loss. ‘To add to the misery of his fate the poor fellow was an excellent swimmer’, he writes, ‘and most probably suffered a horrible & lingering death’.

Language warning: Please note that these sources contain language which is today considered offensive. It has been retained as it is part of the historical record and evidence of past attitudes.

Comments or Questions: