In South Australia

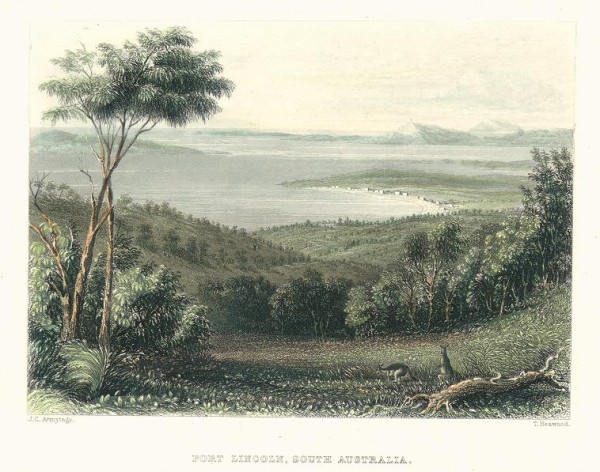

Colonel Light is a relieved man. He has identified the harbour that will become Port Adelaide and is excited by what he sees. ‘[O]ne of the finest little harbours I ever saw is now fairly known’ he writes, adding that it is ‘more extensive, safe and beautiful, than we could even have hoped for.’ He sits down immediately to share his news with the Commissioners in London. In his mind’s eye he can already see it as a busy port, once ‘improved’ by a ‘little human industry’. Since so much of the subsequent history of South Australia stems from this decision, we include a lengthy excerpt from his report here, along with a second report from George Kingston confirming Light’s opinion of the country inland. We can see clearly in this report that Light is by now almost certain that this will be the site of the capital, but he must still go to Port Lincoln to inspect that anchorage before he can confirm it. He is also profoundly relieved to find that the settlers at Holdfast Bay now agree with him. Their early reservations (loudly expressed) have disappeared.

At Holdfast Bay we catch up with Robert Gouger, who has been too busy to write for some time. He and his wife Harriet are settling into their tent, after much laborious trudging back and forth with their possessions along a sandy track from the beach. Harriet is by now advanced in pregnancy and remained on board until the tent was in place. Like all the settlers they are tormented by mosquitoes and flies, but are also rather disconcerted to find other more alarming insects – centipedes, huge ants and a scorpion – invading their tent. Surprisingly, no-one seems to have encountered a snake yet. The climate is also proving more trying than they had anticipated. Gouger is surprised by the intensity of the heat, but even more by the sudden changes of temperature, recording that on one day the temperature ranged from 105E to 50E within 12 hours. It has also been very wet, with ‘frequent gales’ – the same gales that are causing so much frustration to Colonel Light. Gouger is lucky: his tent is a ‘double’, with two layers of canvas. But most of the emigrants have only ‘singles’, which cannot keep out the rain. It is a bedraggled little settlement during the frequent storms.

In Rapid Bay Dr Woodforde is also suffering from the heat. As a man of science, he takes note of the daily temperatures, and on 20 November records that the temperature reaches 123°F (50°C) in his tent during the day, before falling to 60°F (15°C) at night. No wonder they are all feeling weary! Many are also suffering from opthalmia, a painful inflammation of the eyes very common in nineteenth century Australia, although his suggestion that it was caused by the rapid changes in temperature and the glare of the sun, would later prove to be mistaken. Flies were the probable culprit. The next day however Woodforde is sufficiently recovered to venture out shooting again, but strays away from the surveying team and almost runs into a group of ‘strange’ Aboriginal men. It turns out that they have come from Encounter Bay. Woodforde’s comments make it plain that, although he feels confident of the Aboriginal men attached to their settlement, he is still very wary of strangers. ‘[N]ot at all inclined to be eaten I quickly retraced my steps’, he writes, suggesting that he still believes he may encounter cannibals.

On Kangaroo Island John Brown is struggling to keep his animals either confined or healthy. They seem to spend all their time searching for straying animals. Fresh water is still a problem for the settlement too. William Deacon writes enviously that the settlers at Holdfast Bay seem to have ‘plenty of fresh water’, although ‘plenty of mosquitoes’ too. He fervently hopes they will find fresh water soon and receive the malt hops promised by the Company so that they can begin to brew beer. ‘I this day paid 15d [pence] for a bottle of Beer’, he writes. He is still an optimist though, ending his report by assuring the Commissioners ‘I was never better in my life’.

At sea

George Stevenson is still busily drafting legislation for the new settlement. This week he is working on another aspect of the Master and Servants Acts, and, interestingly, on an act to prevent imprisonment for debt. Is it a coincidence that the man credited with the plan for South Australia, Edward Gibbon Wakefield, developed his ideas while imprisoned in Newgate as a debtor? Either way, Stevenson is interrupted in his work by James Fisher who has another epileptic fit. This is a matter of concern to all on board, who are beginning to wonder how his condition will affect his ability to work on arrival.

General relations on board are little improved from the week before. If anything they are worse, since the Captain has once again reduced the water ration by one pint, ostensibly (according to Stevenson) to water his animals. Even Young Bingham Hutchinson records the reduction in the water ration in the first hint we have that he has come to share the general critical view of Hindmarsh. ‘The allowance of water reduced this day to two quarts a head Latin phrase meaning per day. per diem , half of which is consumed in cooking & the other quart is all I am allowed for washing & drinking’, he writes tersely.

Comments or Questions: